The first natural, and certainly the most meaningful, phenomenon was the eruption of the Chilean volcano Puyehue-Cordon del Caulle, situated 100 km NW of Bariloche, last June 4th, 2011. Photos, taken about 30 km away from the crater, give an idea of the size of the cataclysm. The immediate consequence for Bariloche was a solid rain that covered the city and the lake with 12 inches of sand and pumice stone, because, unfortunately, that day the wind was blowing right in the axis of the volcano (310°).

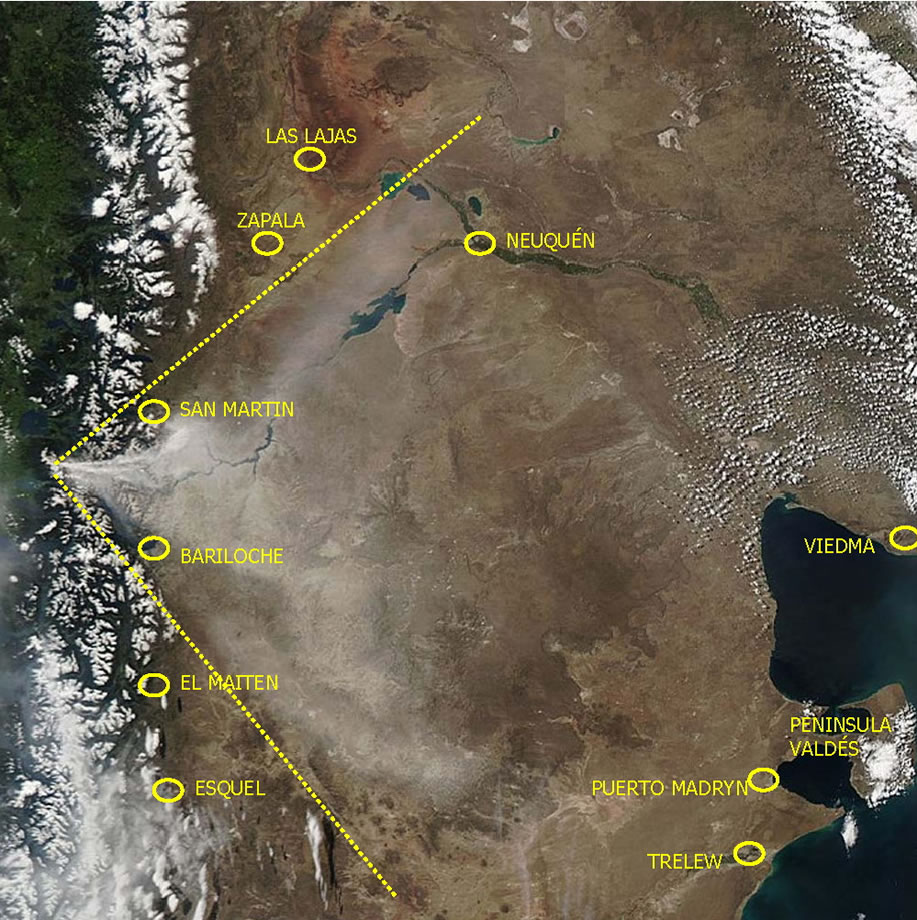

Some days after the explosion, the volcano started spitting very fine, impalpable ashes (as light as icing sugar) sowing this thick, deadly powder along its plume that turned according to the will of the wind and falling to earth along a cone of 90° angle having its bisector oriented precisely W-E and whose edges were, unfortunately, the airports of Bariloche and San Martin de Los Andes, with, as a consequence, the inactivity of one or the other, and the impossibility of flying below 3000m along the 100km that separates these two airports.

The runway remained unusable for four months, the time for rain and snow to make the dust penetrate the soil and for the wind to displace the rest eastward up to Buenos Aires (1600 km), where the airports had to for close several days, like those of South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

Gliders hangar cleaning

Under the ashes, waiting for better times

Of course, you will say “But why the hell did you go there, knowing the situation? “ After long reflection, and consultations with the German team, we decided to go based upon the facts that, on the one hand, no eruption of the neighbouring volcanoes (Llaima and Chaiten in 2008) had lasted more than three months and, on the other hand, the area of influence of the plume had completely spared the neighbouring airports of (B) El Maiten (100 km south), (C) Esquel (200 km south), (D) Zapala (250 km north) so we could have moved the camp there if necessary. Actually, none of the plans B, C or D could be applied. For (A), the runway of El Maiten was too soft to allow the Nimbus to take off with two pilots, which forced me to abandon my passenger on the ground to return by bus, in his flight suit designed for -30°C but with +25° on the ground and not a single penny in his pocket!

Under the ashes, waiting for better times