This is our beach, usually used at the end of January and beginning of February. But we are on October 30, and this augurs the rest of the stay!

We should perhaps talk about climatology rather than meteorology, because even though the short term, that is to say a few days, was quite conventional, the long term was quite different and mostly unpredictable.

From mid-November to mid-January 2017, we had only 7 days of rain (a drama for this area), 31 days of usable wind (30 in 2013), but 23 days of mirror lake, which is a novelty, sad for us but excellent for tourism. Luckily my boat and the trout fishing equipment have fulfilled their duty and we have never eaten as much fish since we rarely came back empty-handed and often with more than one catch.

Our Official Observers relaxing at Puerto Blest. Menu of the day: trout.

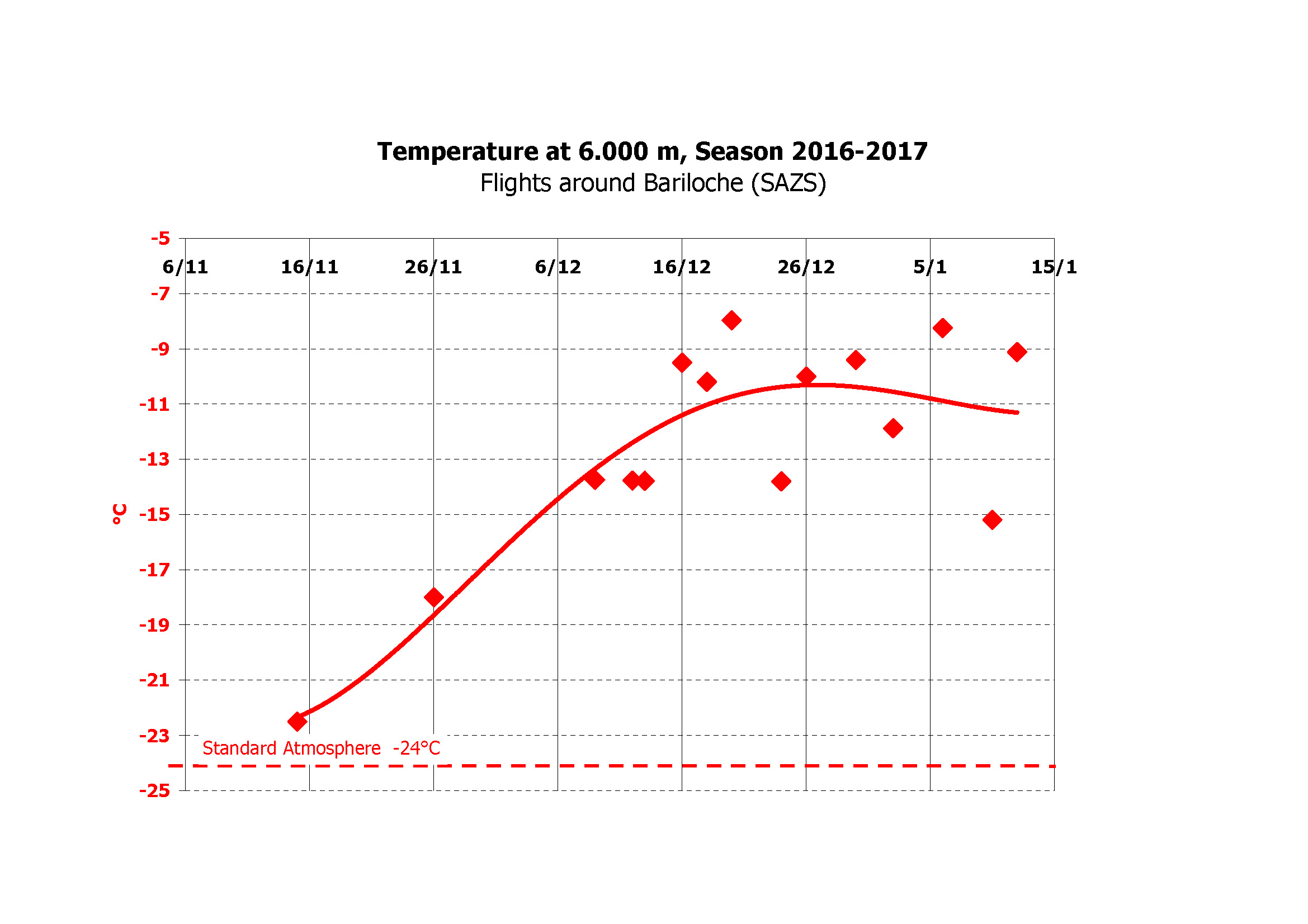

As everywhere on our planet, the ground temperature has significantly risen since our first stay in 2002, probably a few degrees. But at high altitude the situation is a real drama: it continues to increase by about 1°C per year, which is catastrophic for the intensity of the lift, which decreases, and the length of the wave, which increases, and is no longer in phase with the orography. As every year, we measured the temperature around 6,000 m for each flight, then recalculated its at exactly 6,000 m according to the adiabatic law, all shown in the diagram below. Although the dispersion is quite high (each point represents the average of the day’s measurements), it is clear that the average trend between mid-December and mid-January is around -10 to -11°C. It was -12°C in 2013. Remind that the standard temperature at this altitude is -24°C, and it was actually such during our first flights in 2002 – 2003. We even noticed a peak at -5°C at 6,000 m, which is worrisome at this latitude. This is probably why the average vertical lift (Vz) of the waves were generally much lower than those of a decade ago, we had to accept 2 to 3 m/s, sometimes even less, where we previously had between 5 and 8 m/s, for example in the first rebound of the Cordón de Esquel.

For this reason, the best average speeds on FAI tasks (excluding yo-yos OLC which did not interest my pilots) have not exceeded 160 km/h, hence the impossibility of converting flight time into distance.

On the other hand, the hydraulic jumps, of which we shall speak later, and which obey different laws, were in no way affected by this phenomenon, and Vz between 5 and 8 m/s were common (we had 15 m/s in 2002).

November was practically dead, just two local flights in wave and two in thermal. Fifteen years ago the second fortnight of November was that of the big O/R world records. Unlike previous years, the situation continued to improve until our departure on January 16th, with increasingly frequent occurrences of increasingly majestic hydraulic jumps. With unfortunately no forecast for this phenomenon.

The most striking fact of these two months was that, with a few exceptions, Patagonia was divided into three areas: the North, starting 100 km North of Bariloche, including Zapala where the Germans had their base, few windy days and no cloud; the middle, between this sector and 200 km South of Bariloche, quite often windy, sometimes even from the South, with acceptable cloud cover even if sometimes critical for the return; the South, with intense cloud coverage and heavy precipitations. On the North side, Klaus Ohlmann could take advantage of the Stemme cruising characteristics and could often travel to meet the wind with an hour of engine while his companions were roasting under the sun in thermals. On the South side, Jean-Marc Perrin was able to make much less flights with few frights and outlandings in Bariloche under the deluge.

January 10th was an exception and Klaus took the opportunity to try the goal flight distance record of 2,500 km from the South to the North. We had seen the situation coming but moving of our logistics 1,500 km further South would have required three days of preparation including two days driving, plus de-rig and re-rig the Nimbus. We decided to give up. Klaus cleverly took advantage of the turbo-compressed Stemme’s capabilities by making a ferry flight to El Calafate in the South above the cloud cover. However, its starting point was 150 km backwards and against the wind, which made it impossible to achieve the record. We do not know why he did not fly directly with engine to Rio Turbio airport, his start point, which had already been used as a base by Jean-Marc Perrin in previous years. IGC File here.