The first takeoff toward the volcanoes.

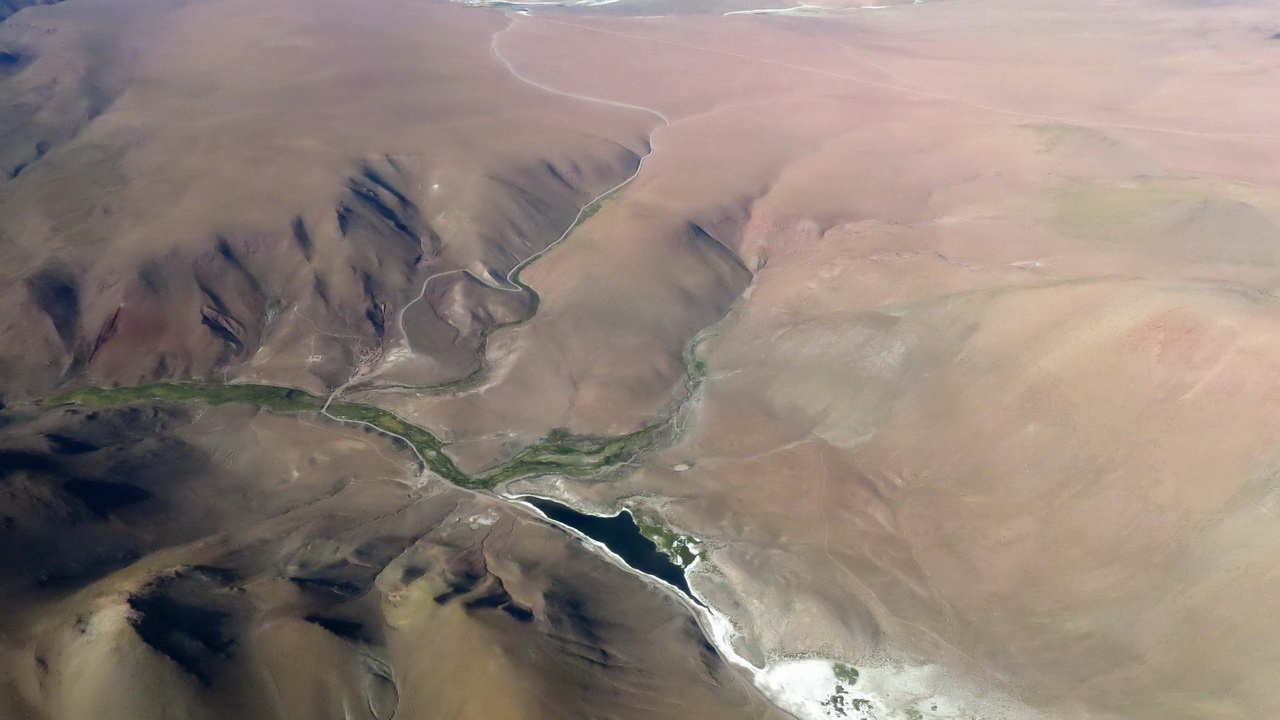

The mythical Licancabur thrones majestically in front of my window every morning, as the air is very clear, it is perfectly visible but is nevertheless 110 km from Calama, and you have to be at its foot at least at 5,000 m, if we are looking for the north side (the sunny side) or the convergence wave. No one knew how our small 90 hp Volkswagen carburetor engine would behave. Admittedly, the flight manual gives a theoretical practical ceiling of 5,300 m. It was therefore necessary to gain 2,500 m in 100 km, or L/D 25 uphill, corresponding to an average climb of 1.2 m/s. Why not, but that was without taking into account the 20 kt afternoon tail breeze which considerably flattened the angle of climb; flying for an hour a few hundred meters above a totally unlandable ground (below photo of the arrival at km 100), without any visible human being or access path, was unsustainable for me. We therefore climbed in circles up to at least 500 m above ground, maintaining 25 L/D for the return in the event of an engine failure, not always obvious with 20 kt headwind.

If it’s not the planet Mars, it’s very much like it. Forget about trying to restart the engine!

The first attempt to catch the wave of volcano Sairecabur.

I was looking to reduce the engine time, find an orographic support working with the light breeze of 10-15 kt which still remained around 5,000 m. After having tried all the micro thermals available, more than an hour of engine and 5,000 m, I have to face the facts, the ridges of Sairecabur do not work, they will never work, in no wind. They are irregular, gullied, slightly inclined, dangerous, the wind is only 15 km/h. What if there was a convergence or a jump on the lee side?

But you have to enter Bolivia through a col at 4,500 m, there may be an armed guard at the border? The engine is running, it will help us maintain our altitude (500 m above ground). Alea Jacta Est, at 4:19 p.m. and 5,100 m, we turn around the mountain (5,950 m) and we position where the convergence should be. Miracle, things are moving! The balance is even positive, the engine does not help us but at least it runs. And a stopped engine is more likely to not start than an already running engine, said Michel Audiard! Ten minutes later and 500 m higher, we can return to glider mode, gliding back via the pass is guaranteed if necessary. Thirty three minutes later, we leave at 7,900 m with only 53 km/h west wind, we made it, the passage is open. It will be exploited by all those who agreed to enter illegally in Bolivia to start the flight. But also to “refuel” on the return and ensure the L/D 25 to Calama. That day, I was so convinced that I would tickle all the other volcanoes “from behind”, and it worked everywhere, like in my book.

On November 7, my first flight over the volcanoes of Atacama, and undoubtedly the first flight in the wake of a volcano, which was the only way to go up to 6,000 m (just below the summit of the volcano Licancabur) to ensure the return without engine. West breeze 25-30 km/h insufficient to make the ridge work, anyway complicated by the perfect conicity of the volcano; but sufficient to generate the wake convergence.

Overflying the ALMA radio telescopes at 200 m AGL.

On November 21, first flight directly to the Cordillera Domeyko, distant only 50 km and whose crossing of the Barros Arana pass grants reaching San Pedro airfield. Good thermal under cumulus then everything goes blue. As the thermals are triggered far away from the volcanoes, I decide to continue via the Altiplano, whose ground is at 4,500 – 4,700 m, which makes me fly over the parabolic antennas of the radio telescope ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter Array) at 200 m ground. Surprise, there is nobody, everything is automated from Santiago, just a few technicians housed in Toconao, below towards the Salar at 2,900 m altitude, more livable. No Prohibited zone on the map, I continue. I hope I haven’t generated a “black hole” in the universe … but it shouldn’t work during the day when the sun is active. Photo below. We will return by overflying the Salar, discovering San Pedro through the air and the salty lagoons where we enjoyed swimming few days earlier. The col Paso Barros Arana is still active with cumulus and gives us 5.200 m, granting the return to Calama with L/D 23.

The configuration of these antennas is equivalent to a 16 km diameter telescope.

The oases of San Pedro de Atacama. The old tourist village is on the left, but the indigenous population lives in other much larger oases, in small farms, called “chacras”.

Dr. Eduardo Coopman.

As soon as we are installed at the airport parking, we learn that there is no AVGAS. We will fly at the beginning with car fuel but on November 12, the engine is missing 500 rpm at takeoff, we will give up. After changing the spark plugs, inspecting the carburetor membranes, and a monstrous torticollis (night work in the cold and wind), no improvement. Preliminary conclusion: it can be the fuel. After telephone contact with the local Aero club, Dr. Coopman, owner of a Piper PA28, offers to drain his aircraft to give us his AVGAS, which apparently solves the problem for today. But tomorrow? This same brave man, dynamic septuagenarian, French-speaking, hospital doctor in Calama, invites us to come and fill up at his house in San Pedro, he would have 1,000 liters of AVAGS legally. We will buy 6 cans and make three trips out and return to his farm with our pick-up, where, with his young wife 42 and his daughter of 14, they raise on six hectares, llamas, alpacas, sheep, goats, chickens , rabbits, ducks, birds, dogs, cats, in total energy and water autonomy. Thank you Eduardo! Maybe a future glider pilot? In any case, an essential strategic support in San Pedro.

Fantastic Dr. Coopman, who drained the tanks of his plane to make us fly!

More an engineer than a med. doctor, he personally designed the energy and water autonomy of his farm.

The sun is not lacking, the solar oven is very efficient. But for the traditional asado, it is always embers.

These lamas seem surprised to see Europeans. They are camelids, like its cousin the alpaca, both crosses between the guanaco and the vicuña, same family as the dromedary and the camel..

This strange desert.

Certainly the driest in the world, between the Cordillera de la Costa and that of Domeyko (see topographic profile), but cold at night (6 – 10 °C in spring) and not very hot in summer (25 – 26 °C max at Calama), altitude 2,000 – 3,000 m, no apparent life except some mining activities, no landings except the Pan American road between the sign posts, practically no oasis nor rain. Totally different situation as soon as we approach the Andes Cordillera, where water comes out frequently, oases are frequent (Calama, San Pedro, Chiu Chiu, Machuca), the plateau is fractured by quebradas (canyons) where rivers flow, the only witnesses of human and animal activity. It was there that the Atacamene tribes settled until the arrival of the Spanish around 1540, building fortified communities called Pukaras including that of Lasana, near Calama, is still on its feet and with a little luck, you will even find a guide to tell the life of that time. Unlike the Europeans, the Incas respected and preserved the Atacamene traditions while providing them with specific supplements to their civilization. On the Argentinian side, the entire indigenous population has been massacred or displaced.

The Rio El Loa Quebrada offers its residents everything they need to survive in the desert, but nothing more.

The Pukara of Lasana, an ancient fortified village along the Rio El Loa, inhabited in the period 400 and 1200 DC, was a marvel of social, cultural and military organization. The arrival of the Spanish around 1540 ended this civilization.

The natives who lived in the Pukara of Chiu-Chiu, 30 km east of Calama, were less lucky than their neighbors in Lasana, because on the orders of Pedro de Valdivia around 1540, they were forced to dismantle their Pukara stone by stone to build this church, dedicated to Saint Francis of Assisi (who lived three centuries earlier). It is considered the oldest church in Chile, it is a historic monument and place of tourism, for the happiness of its 350 inhabitants. The graves belong to local religious dignitaries.

However, the driest desert in the world has a weak point: its proximity to the chain of volcanoes and the Altiplano, which, thanks to the Bolivian winter phenomenon, brings a lot of moisture, but only close to the Altiplano and the volcanoes. For example, on January 21 (so in the middle of the tropical summer), we experienced an incredible Bolivian winter day: the rains were so heavy and so cold that they had to close the col Paso Barros Arana pass, above San Pedro, due to snow!

Who says water says life, and this life therefore resumes at the foot of volcanoes around 4,000 m, along the lagunas and the rios. Tiny villages manage to survive with a little livestock and the few “sporty” tourists on circuits organized mainly from San Pedro. Here are some examples that delighted us.

The small hamlet of Machuca, 4,000 m, about twenty houses entirely in adobe, at the foot of the volcano Putana, along a tiny stream of the same name giving birth to a swamp. To see and live absolutely.

Hundreds of flamingos and a dozen other species of water birds find food there. Many descend to the ocean during winter.

The same laguna of Machuca seen from the sky. Lots of life for very little water.

Lama skewer and “empanada de queso” (cheese cake) for the only two tourists that day in Machuca.

The Andean goose is a very nice little goose that spends a life in couple, just like the condor.

The blue-billed duck, teal of La Puna, lives only in this region

The Andean seagulls are curious and laughing, but wreak havoc in the nests of other birds.

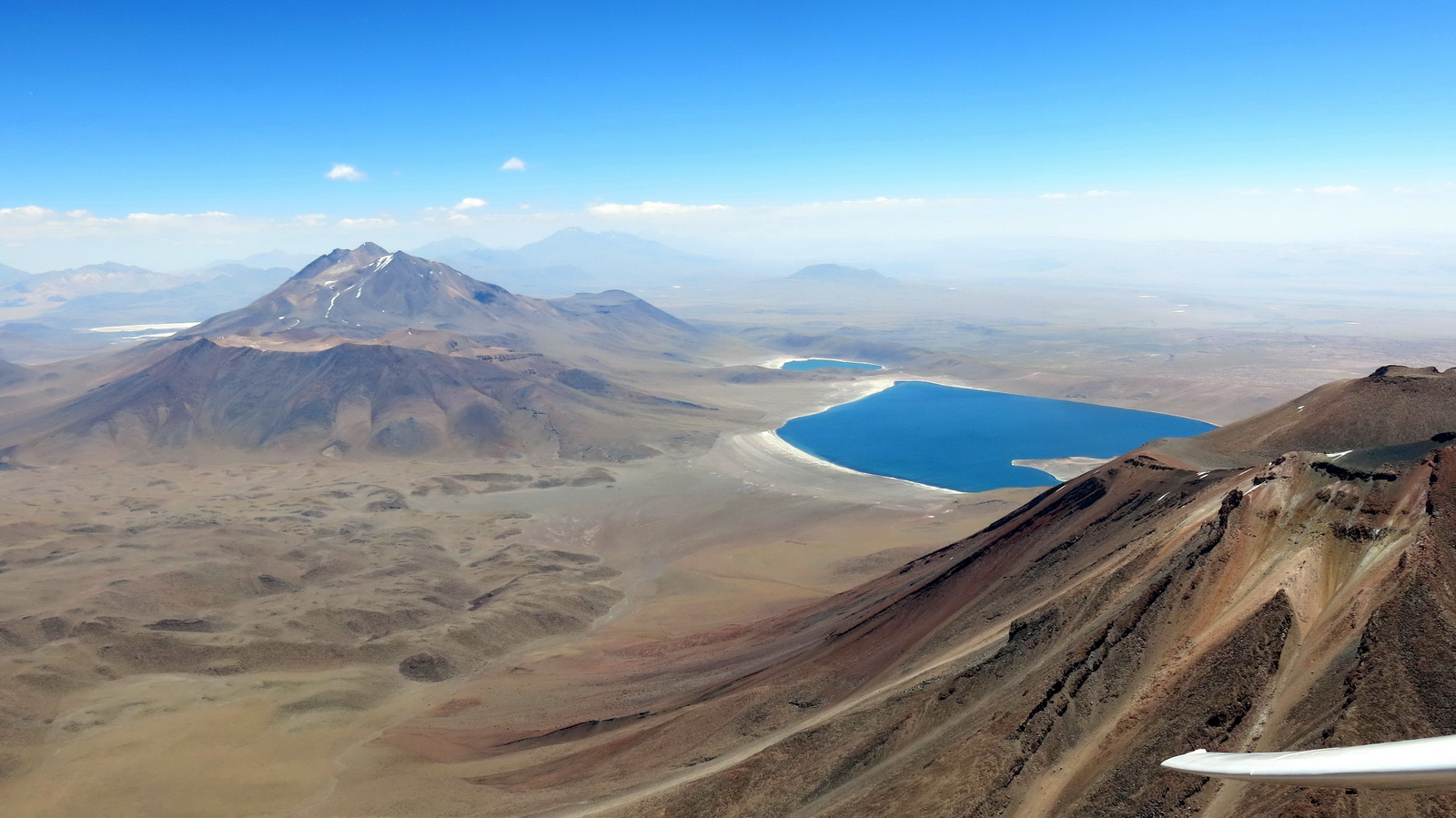

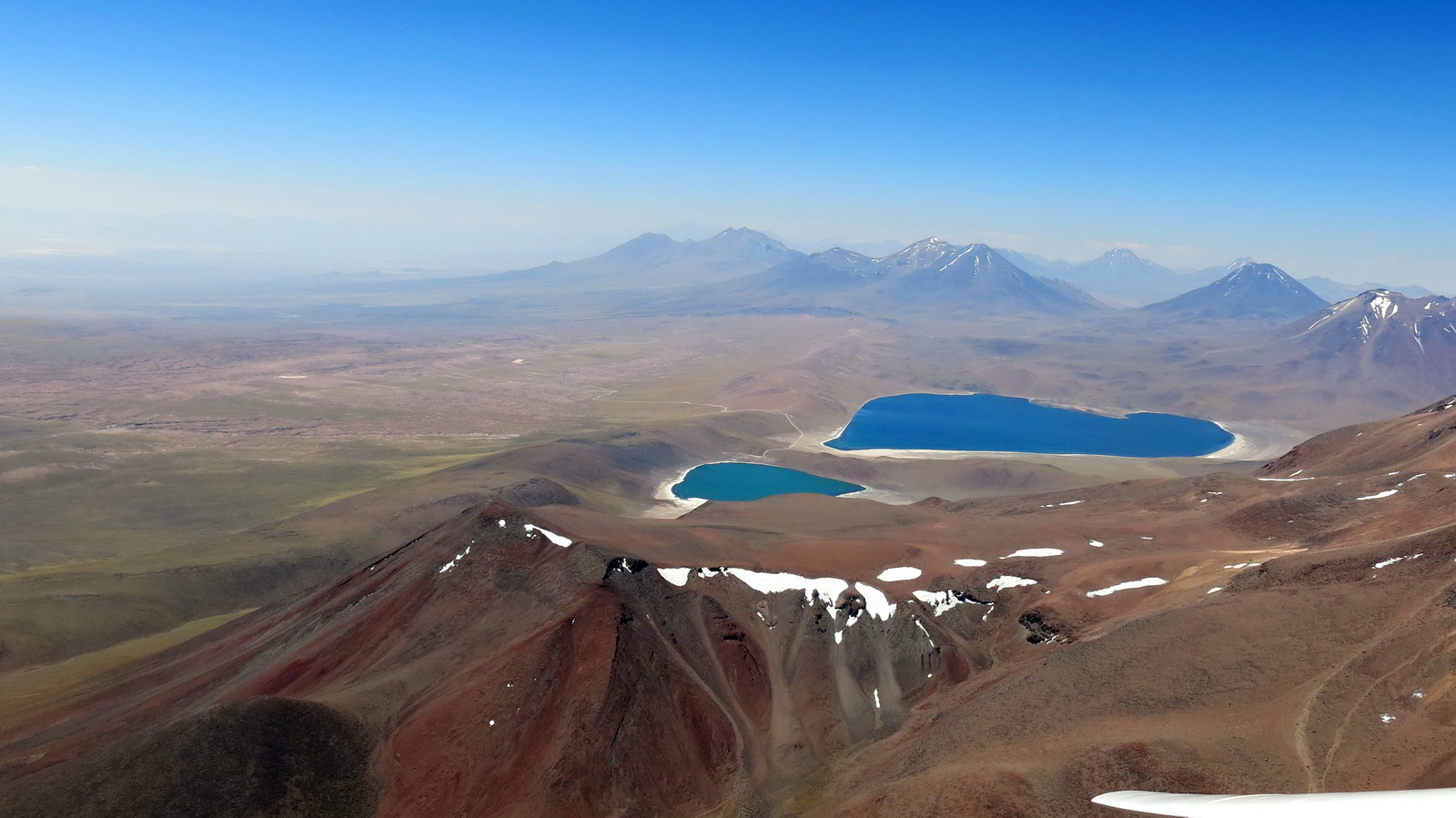

We pass above volcano Miscanti (5,910 m), in front of us the laguna of the same name (altitude 4,140 m) then the volcano Miñiques and its laguna, same altitudes. Two essentials of Atacamene tourism.

These beautiful cumulus in the South with bases between 7,000 and 8,000 m will not be for us, too far away and in Bolivia. Blue thermal only with ceiling around 6,000 m, or 1,000 to 1,500 m AGL.

In the background one can see the volcano Llullaillaco, 6,739 m, the highest volcano in the Cordillera and the second highest in the world.

The Laguna Miscanti, a blue as unique as it is unforgettable. It is teeming with life, the path to get there is deserved, especially by mountain bike!

Miñiques and Miscanti lagoons seen from Miñiques, looking towards the North. All the peaks are around 6,000 m and no more cloud. It is better to turn back home, we will take fly over the Salar along the small ridge which “encloses” the lakes. It will be sufficiently thermally active to ensure a safe return home along the Salar.

As we pass along the Altiplano, we take a look at the ALMA radio telescopes. All the peaks and their clouds are in Bolivia, banned for us as much for political reasons as for safety, and total absence of landing options. This image explains why the volcanoes are thermally inactive (black, charred), while the Altiplano works well, lighter color, rocky (copper?). The color contrasts of this country are fascinating.